"Icarian Games"

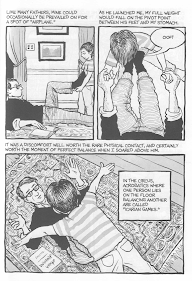

Alison Bechdel begins and ends her graphic novel Fun Home with the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Her perspective of the myth changes, however, as she grows older. In her early childhood, Bechdel is only a spectator of her father’s struggles as she depicts him as both Daedalus and Icarus. Daedalus was a builder; he created the labyrinth for the minotaur and Icarus’ wings. In similar fashion, Bechdel’s father is building the family house, and she calls him “a Daedalus of decor” (Bechdel 6). Bechdel also gives him the title of “artificer.” It implies that unlike Daedalus, her father’s creation is not just a project but a camouflage. Her father is unable to come out as gay because society was not as receptive at the time, so his painstaking work on the house is how he artfully tries to cover his identity. The house is not only how he expresses himself, but it is also his attempt at creating the image of a normal family where he is a normal father. Yet Bechdel never feels like a real family, for her father “treated his furniture like children, and his children like furniture” (14). His efforts to conceal himself trodden Alison’s hope of an actual family and a real relationship with her father. The house, instead, becomes her father’s obsession; it is a representation of his identity.

There are also times when he is like Icarus and flies too close to the sun. Daedalus had warned Icarus that the sun would melt off his wings, but the thrill of flying made Icarus carelessly fly higher until he indeed lost his wings. In Bechdel’s father’s case, it’s when he takes advantage of “young, often straight men…” (94), including their babysitter/gardener Roy. Sometimes he failed to conceal his relations with the young men (like when he ends up on trial for giving alcohol to underage boys), and it seems to make him feel guiltier about his sexual identity. Bechdel’s narration in the beginning shows how her father is in his own world, which she and her family are only a piece of. Her initial interpretation of the myth reveals a disconnect particularly between Bechdel and her father where she is just an observer of the myth.

In the last panels, however, Bechdel’s view of the Icarus and Daedalus myth changes. Rather than her father playing both parts, Bechdel is in the myth as well. She is now Icarus. The novel’s final words are “[but] in the tricky reverse narration that impels our entwined stories, he was there to catch me when I leapt” (232). Her father acted as Daedalus when he helped Bechdel embrace her sexual identity. He provided her with books, like Colette, and shared moments of empathy, like their conversation in the car, one of the first times where she and her father shared their experiences about finding their sexual identity. Bechdel writes, “It was not the sobbing, joyous reunion of Odysseus and Telemachus [Odysseus’s son]” (221), but it was one of the first signs of a relationship between her and her father that she had always hungered for. She also learned from her father’s mistakes and ventured outside of Beech Creek and into a new world in college, allowing her to explore the gay community.

In Bechdel’s childhood, her father was never the traditional father figure, but now he is acting as a parent, a giver of wisdom. She empathizes with her father as she acknowledged the struggles he must have felt, especially during his time. Unlike her initial interpretation of the Icarus and Daedalus myth, Bechdel’s changed perspective in the end of the novel sheds a softer light upon her father.

I found the transformation of Bruce and Alison's relationship one of the most impactful aspects of the novel. In Alison's childhood she very often felt overshadowed, ignored, and just used as a prop in Bruce's illusion of a perfect family. However, in the end of the novel, even after reflecting on many of the negative things Bruce had done, she feels closer to him that when she was young. Not only does she know him better but she also feels supported by him which is a drastic change from her childhood.

ReplyDeleteI think Alison's use of the Daedalus and Icarus myth is a pretty interesting way to describe their relationship, where it's usually unclear who's playing which role. Since Bruce was never much of a father it seems like the few times where is acting like Daedalus are more important to Alison and also help her with her own questions of identity.

ReplyDeleteI thought it was kind of strange and mean how Bruce would treat his children as part of his image to the world. The line “treated his furniture like children, and his children like furniture” lays it out pretty plainly with how his children were only part of the fiction he wanted to put out to the world. It also seems like his later affairs were a result of this concealment and repression. I liked their relationship more later on in the book with how Bruce opened up to Alison a little when she was exploring her sexuality (giving her books, the talk in the car, etc.). Nice post!

ReplyDelete